Even though we use the words hearing and listening interchangeably, the difference in meaning is significant.

Hearing is a sense. Listening is a learned skill.

Hearing is the process, function, or power of perceiving sound.

Listening is paying attention to a message in order to hear it, understand it, and physically or verbally respond to it.

SEVERAL THINGS MUST HAPPEN FOR US TO LISTEN EFFECTIVELY:

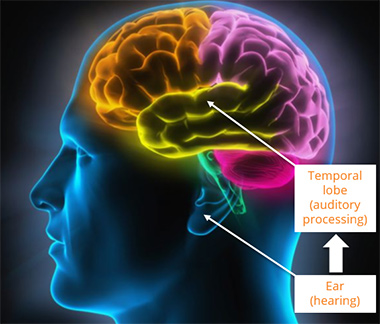

- Sound waves carry spoken words to our ears.

- Sound travels through the outer ear canals (without obstruction) and then through the eardrum and middle ear without being distorted by fluid from colds, infection, or allergies.

- Sound then travels from the middle ear through the inner ear (which must be functioning properly as well) along the auditory nerve to the brain.

- Finally, the brain compares what it hears to previously stored sounds and words in order to make sense of the message and respond accordingly.

“Listening is a crucial skill for young children to acquire. Listening is one of the basic building blocks of language and communication and particularly in the early years of education, one of the main vehicles for a child’s learning.” Eleanor Johnson

Auditory processing disorder (also known as central auditory processing disorder or CAPD) is a condition that makes it hard for kids to recognize subtle differences between sounds in words. It affects their ability to process what other people are saying.

DEFINING AN AUDITORY PROCESSING DISORDER:

Your child passes a hearing test but is diagnosed with an auditory processing disorder. Children with auditory processing disorders typically have normal hearing. But they struggle to process and make meaning of sounds. This is especially true when there are background noises.

Researchers don’t fully understand where things break down between what the ear hears and what the brain processes. But the result is clear: children with auditory processing disorder can have trouble making sense of what other people say.

Typically, the brain processes sounds seamlessly and almost instantly. Most people can quickly interpret what they hear. But with an auditory processing disorder, a glitch delays or “scrambles” that process.

To a child with CAPD, “Tell me how the chair and the couch are alike” might sound like “Tell me how a cow and hair are like.”

The problem lies with understanding the sounds of spoken language, not the meaning of what’s being said.

Some educators and other professionals’ question or doubt a diagnosis of CAPD. Not all professionals see it as a specific disorder. The medical profession didn’t start seriously studying CAPD in children until 1977. Four decades later, there’s still confusion about CAPD.

The number of children with CAPD is estimated to be between 2 – 7 percent. Some experts estimate that boys are twice as likely as girls to have auditory processing disorder, but there’s no solid research to prove that.

WHAT ARE SYMPTOMS OF AN AUDITORY PROCESSING DISORDER?

“The kids we see are having difficulty following directions,” explains Rachel Cortese, a speech-language pathologist at the Child Mind Institute. “They ask for repetition a lot. They seem to just kind of miss things in conversations. From testing we know that their ear is hearing the signal. It’s attending to the auditory information. But they have glitches when the brain is not assigning meaning—or the right meaning—to that signal.”

The term auditory processing refers to how the brain perceives and interprets sound information. Several skills determine auditory processing ability—or listening success. They develop in a general four step hierarchy, but all work together and are essential for daily listening. Although researchers do not agree on the exact hierarchy of skills, they generally agree on what skills are essential for auditory processing success (Cochlear Americas, 2009; Johnson et al., 1997; Nevins & Garber, 2006; Roeser & Downs, 2004; Stredler-Brown & Johnson, 2004).

Children with CAPD can have weaknesses in one, some or all of these areas:

AUDITORY AWARENESS

• Auditory Awareness – the ability to detect sound

• Sound Localization – the ability to locate the sound source

• Auditory Attention / Auditory Figure-Ground – the ability to attend to important auditory information including attending amid competing background noise. It would be like sitting at a party and not being able to hear the person next to you because there’s so much background chatter

AUDITORY DISCRIMINATION

• Auditory Discrimination of Segmentals – the ability to detect differences between specific speech sounds. The words seventy and seventeen may sound alike, for instance

• Auditory Discrimination of Environmental Sounds – the ability to detect differences between sounds in the environment

• Auditory Discrimination of Suprasegmentals – the ability to detect differences in non-phoneme (sound) aspects of speech including rate, intensity, duration, pitch, and overall prosody

AUDITORY IDENTIFICATION

• Auditory Identification (Auditory Association) – the ability to attach meaning to sounds and speech

• Auditory Feedback/Self-Monitoring – the ability to change speech production based on information you get from hearing yourself speak

• Auditory Discrimination of Segmentals – the ability to detect differences between specific speech sounds. The words seventy and seventeen may sound alike, for instance

• Phonological Awareness (Auditory Analysis) – the ability to identify, blend, segment, and manipulate oral language structure

AUDITORY COMPREHENSION

• Auditory Comprehension – the ability to understand longer auditory messages, including engaging in conversation, following directions, and understanding stories

• Auditory Closure – the ability to make sense of auditory messages when a piece of auditory information is missing; filling in the blanks

• Auditory Memory – the ability to retain auditory information both immediately and after a delay

• Linguistic Auditory Processing – the ability to interpret, retain, organize, and manipulate spoken language for higher level learning and communication

CHILDREN WITH APD USUALLY HAVE AT LEAST SOME OF THE FOLLOWING SYMPTOMS:

- Find it hard to follow spoken directions, especially multi-step instructions

- Ask speakers to repeat what they’ve said, or saying, “huh?” or “what?”

- Be easily distracted, especially by background noise or loud and sudden noises

- Have trouble with reading and spelling, which require the ability to process and interpret sounds

- Struggle with oral (word) math problems

- Find it hard to follow conversations

- Have poor musical ability

- Find it hard to learn songs or nursery rhymes

- Have trouble remembering details of what was read or heard

CAPD can affect the child in many spheres of life. Communication, academics (particularly reading, writing and spelling) and social skills can all be impacted. Experts agree that children can learn to work around challenges they face. However, CAPD can present lifelong difficulties if it isn’t diagnosed and managed.

HOW CAN PROFESSIONALS HELP WITH AN AUDITORY PROCESSING DISORDER?

There’s more than one method for helping kids with CAPD. A diagnosis can be made by a qualified Speech-Language Therapist. Management methods include:

- Speech Therapy sessions: Speech therapists can provide exercises and training to build children’s’ ability to identify sounds and develop conversational and listening skills.

- Preferential seating: Seating children with CAPD in the front of the room and away from distractions can help them focus.

- Improved acoustics: Closing doors and windows minimizes outside noise.

- Assistive technology: An amplification system, such as a wireless FM system, reduces background noise and poor acoustics. The child wears a headset and the teacher wears a clip-on microphone.

- Classroom visuals: The teacher uses images and gestures to reinforce the child’s understanding and memory.

WHAT CAN BE DONE AT HOME TO HELP?

- Provide a quiet spot for studying, with background noise kept to a minimum.

- Have your child look at you when you’re speaking.

- Use simple, one-step directions.

- Speak at a slightly slower rate and at a slightly higher volume.

- Ask your child to repeat directions back to you. If he’ll need to act on the directions later, ask him to write notes to remind himself.

- Dangerous Decibels, Noise induced hearing loss in children - June 14, 2019

- Listening to Learn - April 17, 2019

- Listen Up! What’s the big deal with childhood hearing loss? - February 8, 2019

2 thoughts on “Listening to Learn”

For someone who is hearing impaired and more, this article was extremely helpful and insightful.

This article is very insightful